TDD and Testing Behavior

- January 24, 2024 |

- 11 min read

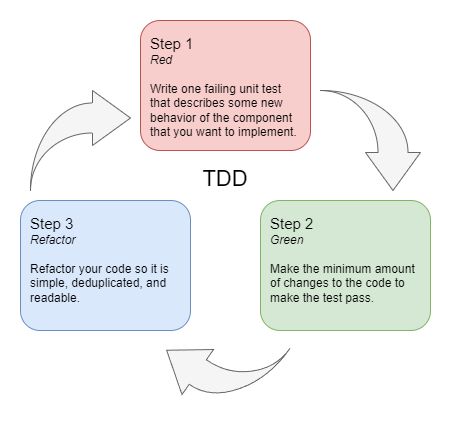

Red, Green, Refactor

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is the practice of writing a failing unit test before writing the code to make the test pass, then cleaning up your code. This is the "red, green, refactor" cycle.

It helps with clarity of thought, increases flow, and results in modular designs that are maintainable. You can probably tell I'm a fan. It's one of the practices that has helped me become a better software engineer over the years. While there are a lot of resources out there to learn about TDD, most of them gloss over an important aspect that makes it much more effective: it matters what you try to test.

Test the Behavior

For TDD to be effective it's important to test the behavior of a component instead of its internal implementation details. This allows changing the component's internal logic without changing its tests. If the component's interface to other components in the system does not change and it can be used the same way as before, then the tests should not need to change either. This allows each individual component of the system to be enhanced, fixed, refactored, rebuilt using a different technology, or even completely replaced with minimal changes to the unit tests.

If the tests are tightly coupled to the internal implementation of a component, then it makes it difficult to modify the component without also modifying the tests. By focusing on only testing the behavior of a component, the unit tests should not be touched at all when changing its internal implementation. Instead, the tests become an important tool to verify that the internal change has not broken the component's behavior.

Component Interfaces

Whenever we build a system, be it large or small, we should break it down into components that each have a unique responsibility. This modularity provides a lot of benefits like easier restructuring, simplicity, maintainability, testability, reducing the cognitive load of software engineers, and more. By identifying the components, we're also defining the boundaries between them and the interfaces they use to communicate with each other.

For each component we should strive to make it easy to change the internal implementation of the component, but we should make it a bit harder to change the interfaces between them. These interfaces are the components' API contracts. The hard part is figuring out the granularity of the components and their responsibility. This comes with experience and depends on many factors. There are many schools of thought on how to break down a system and identify its components (e.g. domain-driven design, event storming, event modeling, clean architecture, etc.), but I generally recommend designing it out visually and running through a few of the most important user scenarios. If you find the current design difficult and complicated, try a different one and keep iterating until you find one that works well.

With some practice, you'll get better at identifying reasonable component boundaries.

Example Repository Implementation

One component boundary I find particularly useful encapsulates access to persistent data using the repository pattern. When building a feature that requires storing and retrieving data, it's usually beneficial to isolate the details of the database technology from the application logic. A repository's single responsibility is to manage the persistent data for an application (or a portion of it).

Let's build a simple repository in Go that shows the difference between the bad implementation-driven vs the good behavior-driven approaches to writing tests. We'll create a repository that saves and retrieves users. Each user only has a name, and just for simplicity we'll "persist" the data in-memory using a map, but you can imagine a DB engine, file system, or object store instead.

Both approaches are shown below:

- Implementation-driven approach to testing (Don't do it like this!)

- Behavior-driven approach to testing (Do it like this, instead!)

Here's the code from these examples if you want to compare the results side-by-side: github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior

Implementation-driven approach to testing

Don't do it like this!

Here's what a user looks like:

File: user.go

package app

type User struct {

Name string

}

And here's a stub user repo to start with:

File: repo/users.go

package repo

type Users struct{}

Save a User

Let's start with saving a user in the repo. We want a Save() method that accepts a user and returns a possible error. We'll write a test for a repo method Save() that we haven't written yet, so it will fail to compile initially.

Test: store a user by name to an empty map

Here's our first failing test, setup with a common table-driven test structure that I find useful:

Red Step 1

File: repo/users_test.go

package repo

import (

app "github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior/implementation-driven"

"reflect"

"testing"

)

func TestUser_Save(t *testing.T) {

type args struct {

user app.User

}

tests := []struct {

name string

repo Users

args args

want Users

wantErr error

}{

{

name: "store a user by name to an empty map",

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Ender"},

},

want: Users{

map[string]app.User{

"Ender": {Name: "Ender"},

},

},

},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

err := tt.repo.Save(tt.args.user)

if !reflect.DeepEqual(err, tt.wantErr) {

t.Errorf("Save() error = %v, wantErr %v", err, tt.wantErr)

return

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(tt.repo, tt.want) {

t.Errorf("Save() = %+v, want %+v", tt.repo, tt.want)

}

})

}

}

This test will fail to compile, so let's write the code to make it pass:

Green Step 2

File: repo/users.go

package repo

import app "github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior/implementation-driven"

type Users struct {

users map[string]app.User

}

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

u.users = map[string]app.User{

user.Name: user,

}

return nil

}

Alright, our test passes!

Refactor Step 3

The next step is to refactor our code and clean it up, but the code is so simple at this point let's move on to the next test cycle.

Test: store a new user by name to a map that already has a user

Red Step 1

File: repo/users_test.go (partial)

// ...

{

name: "store a new user by name to a map that already has a user",

repo: Users{

map[string]app.User{

"Ender": {Name: "Ender"},

},

},

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Valentine"},

},

want: Users{

map[string]app.User{

"Ender": {Name: "Ender"},

"Valentine": {Name: "Valentine"},

},

},

},

// ...

This test will fail because of our overly-simplistic implementation from the first test, so let's fix that:

Green Step 2

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

if u.users == nil {

u.users = map[string]app.User{

user.Name: user,

}

} else {

u.users[user.Name] = user

}

return nil

}

This makes our test pass, but now we have a bit of cruft in our logic so let's simplify it:

Refactor Step 3

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

if u.users == nil {

u.users = make(map[string]app.User, 1)

}

u.users[user.Name] = user

return nil

}

And our test is still passing!

Test: return an error if the user's name already exists

If a user already exists in our repo with the same name, we want an error to be returned so let's write a test for that:

Red Step 1

File: repo/users_test.go (partial)

// ...

{

name: "return an error if the user's name already exists",

repo: Users{

map[string]app.User{

"Peter": {Name: "Peter"},

},

},

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Peter"},

},

want: Users{

map[string]app.User{

"Peter": {Name: "Peter"},

},

},

wantErr: fmt.Errorf("user name \"Peter\" already exists"),

},

// ...

Green Step 2

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

if _, exists := u.users[user.Name]; exists {

return fmt.Errorf("user name \"Peter\" already exists")

}

if u.users == nil {

u.users = make(map[string]app.User, 1)

}

u.users[user.Name] = user

return nil

}

Notice the naive hard-coded error message? It's the simplest code that makes our test pass, but we want to clean that up in the refactor step:

Refactor Step 3

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

if _, exists := u.users[user.Name]; exists {

return fmt.Errorf("user name %q already exists", user.Name)

}

if u.users == nil {

u.users = make(map[string]app.User, 1)

}

u.users[user.Name] = user

return nil

}

Here's the code for this approach

Is there a better way?

At this point, we've only written tests and functionality around saving a user. We could continue on to build out the functionality to retrieve users taking the same approach. It's great that we're using the basic TDD red, green, refactor cycle, but first think about what would happen if we needed to change the implementation. Could we add a user ID field index? Or upgrade to a persistent DB instead of in-memory? In either of these scenarios we'd need to completely rewrite all of these tests because they are tightly coupled to the internal implementation of the user repo.

I want to show you a better way.

Behavior-driven approach to testing

Let's start off fresh with our basic user and repo stub:

File: user.go

package app

type User struct {

Name string

}

File: repo/users.go

package repo

type Users struct{}

Save a User

Just like before, let's start with saving a user in the repo. But instead of thinking in terms of the steps that the repo will need to take to accomplish this, think about how we want the repo to behave when it is used. How does this change our perspective of the Save() method? Well, what behavior do we want from the repo when we save a user? After we save a user, we should then be able to get it back! If we think of it this way, then it doesn't matter how the repo stores the data. It only matters that if we save it, we can then get the same data back.

Let's use TDD to write our first behavioral test.

Spec: Should save a user to an empty repo

When writing this first test, we need to spend a bit more time thinking about the interface to get a user back out of the repo, too. In this example we're going to use a GetAll() function that returns a slice of all the users in the repo. We could also retrieve a single user by name, or some other way that aligns with the other use-cases.

Red Step 1

Notice the package name is repo_test instead of just repo. We want to test the repo's interface so we only want to access its publicly exported methods. Go allows appending _test to the package name to enforce this.

File: repo/users_test.go

package repo_test

import (

app "github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior/behavior-driven"

"github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior/behavior-driven/repo"

"reflect"

"testing"

)

func TestUser_Save(t *testing.T) {

type args struct {

user app.User

}

tests := []struct {

name string

repo repo.Users

args args

wantErr error

wantUsers []app.User

}{

{

name: "should save a user to an empty repo",

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Ender"},

},

wantUsers: []app.User{{Name: "Ender"}},

},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

err := tt.repo.Save(tt.args.user)

if !reflect.DeepEqual(err, tt.wantErr) {

t.Errorf("Save() error = %v, wantErr %v", err, tt.wantErr)

return

}

got, err := tt.repo.GetAll()

if err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(got, tt.wantUsers) {

t.Errorf("After Save(), GetAll() = %+v, wantUsers %+v", got, tt.wantUsers)

}

})

}

}

Green Step 2

To make this test pass, we need both a Save() and GetAll() method. Remember, we're just writing the bare minimum code to make the test pass in this step!

File: repo/users.go

package repo

import (

app "github.com/benjohns1/tdd-and-testing-behavior/behavior-driven"

)

type Users struct{}

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

return nil

}

func (u *Users) GetAll() ([]app.User, error) {

return []app.User{{Name: "Ender"}}, nil

}

Refactor Step 3

Now we refactor our naive code into little better solution. And we have our test to verify it is still correct:

File: repo/users.go (partial)

type Users struct {

user app.User

}

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

u.user = user

return nil

}

func (u *Users) GetAll() ([]app.User, error) {

return []app.User{u.user}, nil

}

Spec: Should save a user to a repo that already has a user in it

Red Step 1

File: repo/users_test.go (partial)

// ...

{

name: "should save a user to a repo that already has a user in it",

repo: func() repo.Users {

r := repo.Users{}

if err := r.Save(app.User{

Name: "Ender",

}); err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

return r

}(),

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Valentine"},

},

wantUsers: []app.User{

{Name: "Ender"},

{Name: "Valentine"},

},

},

// ...

Green Step 2

File: repo/users.go (partial)

type Users struct {

users []app.User

}

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

u.users = append(u.users, user)

return nil

}

func (u *Users) GetAll() ([]app.User, error) {

return u.users, nil

}

Refactor Step 3

Let's make our repo encapsulation a bit better by not allowing mutation of the repo's internal slice:

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) GetAll() ([]app.User, error) {

out := make([]app.User, 0, len(u.users))

for _, user := range u.users {

out = append(out, user)

}

return out, nil

}

Spec: Should fail if a user's name already exists

Red Step 1

File: repo/users_test.go (partial)

// ...

{

name: "should fail if a user's name already exists",

repo: func() repo.Users {

r := repo.Users{}

if err := r.Save(app.User{

Name: "Peter",

}); err != nil {

t.Fatal(err)

}

return r

}(),

args: args{

user: app.User{Name: "Peter"},

},

wantUsers: []app.User{{Name: "Peter"}},

wantErr: fmt.Errorf("user name \"Peter\" already exists"),

},

// ...

Green Step 2

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

for _, current := range u.users {

if current.Name == user.Name {

return fmt.Errorf("user name \"Peter\" already exists")

}

}

u.users = append(u.users, user)

return nil

}

Refactor Step 3

Clean up the naive error message:

File: repo/users.go (partial)

func (u *Users) Save(user app.User) error {

for _, current := range u.users {

if current.Name == user.Name {

return fmt.Errorf("user name %q already exists", user.Name)

}

}

u.users = append(u.users, user)

return nil

}

Here's the code for this approach

Conclusion

Take a look at your implementation using the behavior-driven approach. For the same amount of effort, we've also implemented retrieving users from the repo, too. Now let's ask the same questions we did earlier: Could we add a user ID field index? Or upgrade to a persistent DB instead of in-memory? Both of these scenarios could be accomplished without modifying our existing tests (apart from maybe some test setup to implement a real DB backend).

Our behavior tests are much more robust, and they're validating what we really care about: the behavior of the repo. If the interface changes we want the tests to break because that means we've changed the repo's behavior. If we need to refactor the internals of the repo, we can use our tests to be confident that we haven't broken any existing use-cases.

TDD is an incredibly useful practice but only if you are testing behavior!